Building Data-Driven Development

A few weeks ago I had to honor to speak at my group’s “Global Empowerment Meeting” about my research on data science and economic development. I’m linking here the Youtube video of my talk and my transcript for those who want to follow it. The transcript is not 100% accurate given some last minute edits — and the fact that I’m a horrible presenter 🙂 — but it should be good enough. Enjoy!

We think that the big question of this decade is on data. Data is the building blocks of our modern society. We think in development we are not currently using enough of these blocks, we are not exploiting data nearly as much as we should. And we want to fix that.

Many of the fastest growing companies in the world, and definitely the ones that are shaping the progress of humanity, are data-intensive companies. Here at CID we just want to add the entire world to the party.

So how do we do it? To fix the data problem development literature has, we focus on knowing how the global knowledge building looks like. And we inspect three floors: how does knowledge flow between countries? What lessons can we learn inside these countries? What are the policy implications?

To answer these questions, we were helped by two big data players. The quantity and quality of the data they collect represent a revolution in the economic development literature. You heard them speaking at the event: they are MasterCard – through their Center for Inclusive Growth – and Telefonica.

Let’s start with MasterCard, they help us with the first question: how does knowledge flow between countries? Credit card data answer to that. Some of you might have a corporate issued credit card in your wallet right now. And you are here, offering your knowledge and assimilating the knowledge offered by the people sitting at the table with you. The movements of these cards are movements of brains, ideas and knowledge.

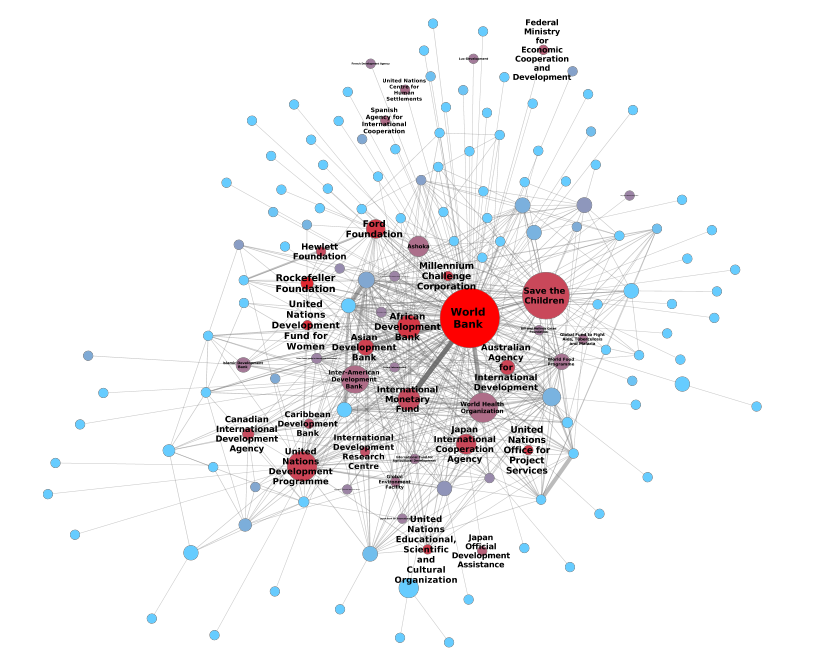

When you aggregate this at the global level you can draw the map of international knowledge exchange. When you have a map, you have a way to know where you are and where you want to be. The map doesn’t tell you why you are where you are. That’s why CID builds something better than a map.

We are developing a method to tell why people are traveling. And reasons are different for different countries: equity in foreign establishments like the UK, trade partnerships like Saudi Arabia, foreign greenfield investments like Taiwan.

Using this map, it is easy to envision where you want to go. You can find countries who have a profile similar to yours and copy their best practices. For Kenya, Taiwan seems to be the best choice. You can see that, if investments drive more knowledge into a country, then you should attract investments. And we have preliminary results to suggest whom to attract: the people carrying the knowledge you can use.

The Product Space helps here. If you want to attract knowledge, you want to attract the one you can more easily use. The one connected to what you already know. Nobody likes to build cathedrals in a desert. More than having a cool knowledge building, you want your knowledge to be useful. And used.

There are other things you can do with international travelers flows. Like tourism. Tourism is a great export: for many countries it is the first export. See these big portion of the exports of Zimbabwe or Spain? For them tourism would look like this.

Tourism is hard to pin down. But it is easier with our data partners. We can know when, where and which foreigners spend their money in a country. You cannot paint pictures as accurate as these without the unique dataset MasterCard has.

Let’s go to our second question: what lessons can we learn from knowledge flows inside a country? Telefonica data is helping answering this question for us. Here we focus on a test country: Colombia. We use anonymized call metadata to paint the knowledge map of Colombia, and we discover that the country has its own knowledge departments. You can see them here, where each square is a municipality, connecting to the ones it talks to. These departments correlate only so slightly with the actual political boundaries. But they matter so much more.

In fact, we asked if these boundaries could explain the growth in wages inside the country. And they seem to be able to do it, in surprisingly different ways. If you are a poor municipality in a rich state in Colombia, we see your wage growth penalized. You are on a path of divergence.

However, if you are a poor municipality and you talk to rich ones, we have evidence to show that you are on a path of convergence: you grow faster than you expect to. Our preliminary results seem to suggest that being in a rich knowledge state matters.

So, how do you use this data and knowledge? To do so you have to drill down at the city level. We look not only at communication links, but also at mobility ones. We ask if a city like Bogota is really a city, or different cities in the same metropolitan area. With the data you can draw four different “mobility districts”, with a lot of movements inside them, and not so many across them.

The mobility districts matter, because combining mobility and economic activities we can map the potential of a neighborhood, answering the question: if I live here, how productive can I be? A lot in the green areas, not so much in the red ones.

With this data you can reshape urban mobility. You know where the entrance barriers to productivity are, and you can destroy them. You remodel your city to include in its productive structure people that are currently isolated by commuting time and cost. These people have valuable skills and knowhow, but they are relegated in the informal sector.

So, MasterCard data told us how knowledge flows between countries. Telefonica data showed the lessons we can learn inside a country. We are left with the last question: what are the policy implications?

So far we have mapped the landscape of knowledge, at different levels. But to hike through it you need a lot of equipment. And governments provide part of that equipment. Some in better ways than others.

To discover the policy implications, we unleashed a data collector program on the Web. We wanted to know how the structure of the government in the US looks like. Our program returned us a picture of the hierarchical organization of government functions. We know how each state structures its own version of this hierarchy. And we know how all those connections fit together in the union, state by state. We are discovering that the way a state government is shaped seems to be the result of two main ingredients: where a state is and how its productive structure looks like.

We want to establish that the way a state expresses its government on the Web reflects the way it actually performs its functions. We seem to find a positive answer: for instance having your environmental agencies to talk with each other seems to work well to improve your environmental indicators, as recorded by the EPA. Wiring organization when we see positive feedback and rethinking them when we see a negative one is a direct consequence of this Web investigation.

I hope I was able to communicate to you the enthusiasm CID discovered in the usage of big data. Zooming out to gaze at the big picture, we start to realize how the knowledge building looks like. As the building grows, so does our understanding of the world, development and growth. And here’s the punchline of CID: the building of knowledge grows with data, but the shape it takes is up to what we make of this data. We chose to shape this building with larger doors, so that it can be used to ensure a more inclusive world.

By the way, the other presentations of my session were great, and we had a nice panel after that. You can check out the presentations in the official Center for International Development Youtube channel. I’m embedding the panel’s video below: