A moral imperative that wealthy communities have — in my opinion — is to ensure economic convergence: to help the poorer economies to have a stronger economic growth so that everyone is lifted out of poverty*. There is a lot of debate on whether economic convergence is actually happening (some say yes, others no) — and, if so, at which scale (global, national, regional?). In my little contribution to the question I show that — if convergence happens — it is not via traditional institutional channels, but via participation in the global social network. Which is terrible news in these days, since we’re experiencing an unprecedented collapse in this web of relations due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

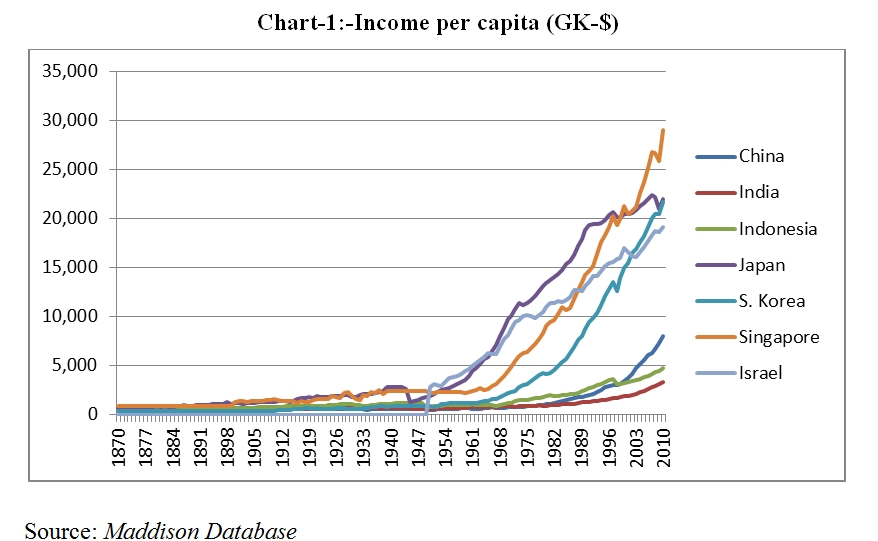

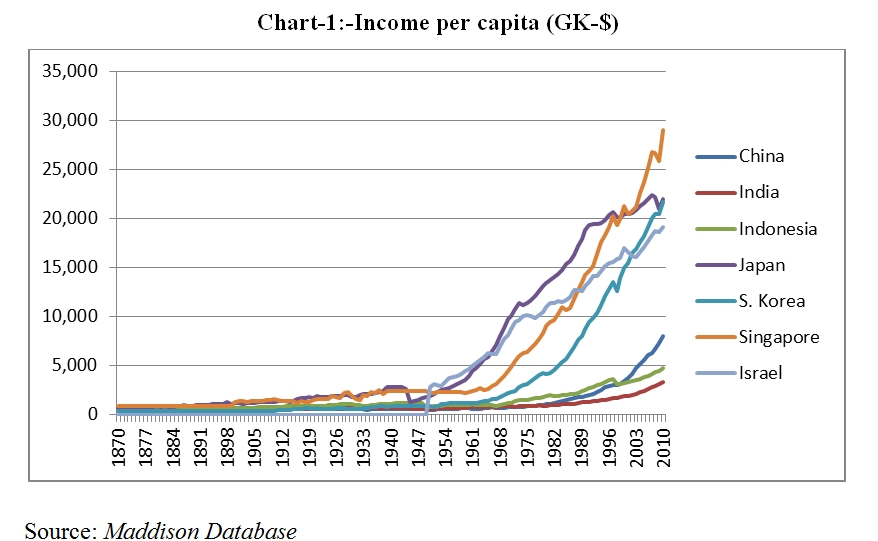

An example of economic divergence: some countries like Singapore are now 6X richer than other countries that had a comparable level of income in the late 1800. Image from EconoTimes.

This message comes from a paper I wrote a while ago with Tim Cheston and Ricardo Hausmann: “Institutions vs. Social Interactions in Driving Economic Convergence: Evidence from Colombia“. I never mentioned it because it is just a working paper, so all conclusions should be taken with a boatload of grains of salt. But it is an interesting perspective on the consequences of these troubling times — plus it foreshadows another post I’m planning for the future, so stay tuned 🙂

The idea is simple: we want to know whether economic convergence happens in Colombia. If it does, we want to show that its driving force is the participation in social networks. In other words, economic growth is a matter of connecting skillful people with people possessing capital. We need to make sure we’re not confusing our “social relationships” explanation with the ability of some states to be better at providing public goods and redistributing wealth from the rich municipalities to the poor ones.

The public institutions hypothesis seems natural: if you have good politicians, they would write good laws which will support their population’s prosperity. Bad politicians would just be inept, or even corrupt. In this hypothesis, poor municipalities in rich (= well managed) regions should grow faster than poor municipalities in poor (= badly managed) regions. Our hypothesis, instead, proposes that poor municipalities with strong social connections to rich municipalities should grow faster than poor municipalities without such connections. For this we need to know two things: in which administrative region a municipality is (easy!) and to which social group of municipalities it belongs.

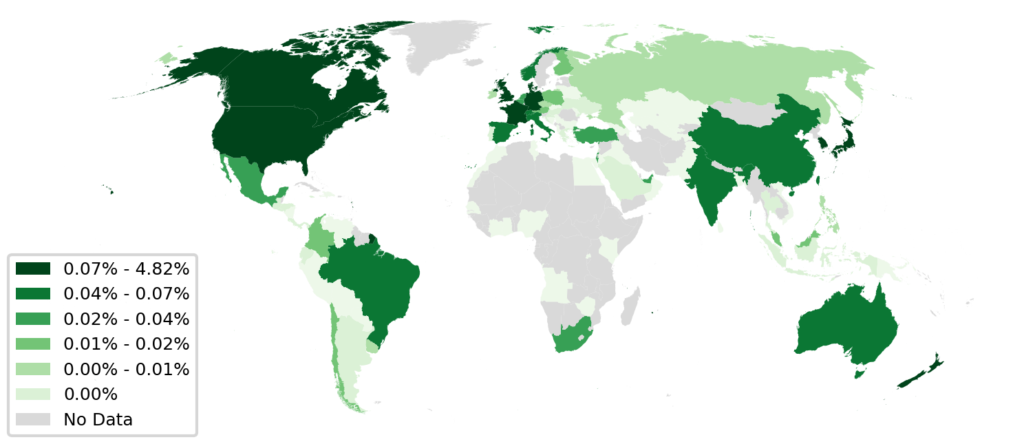

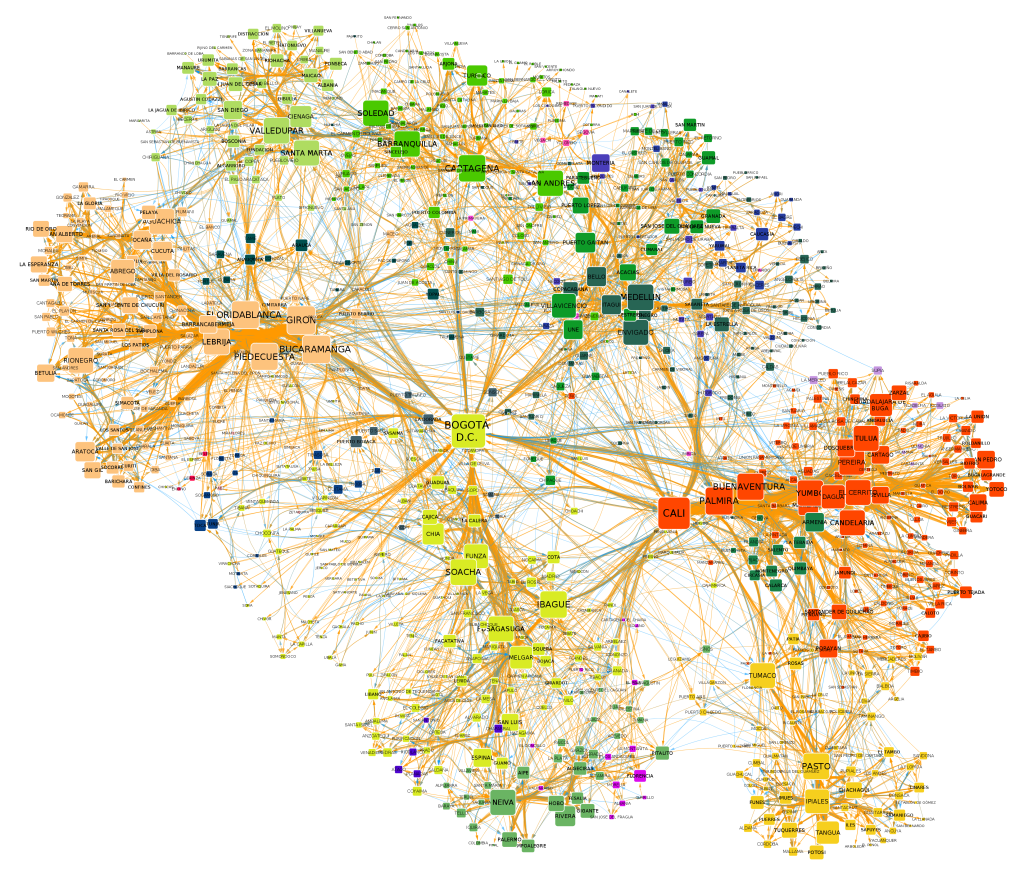

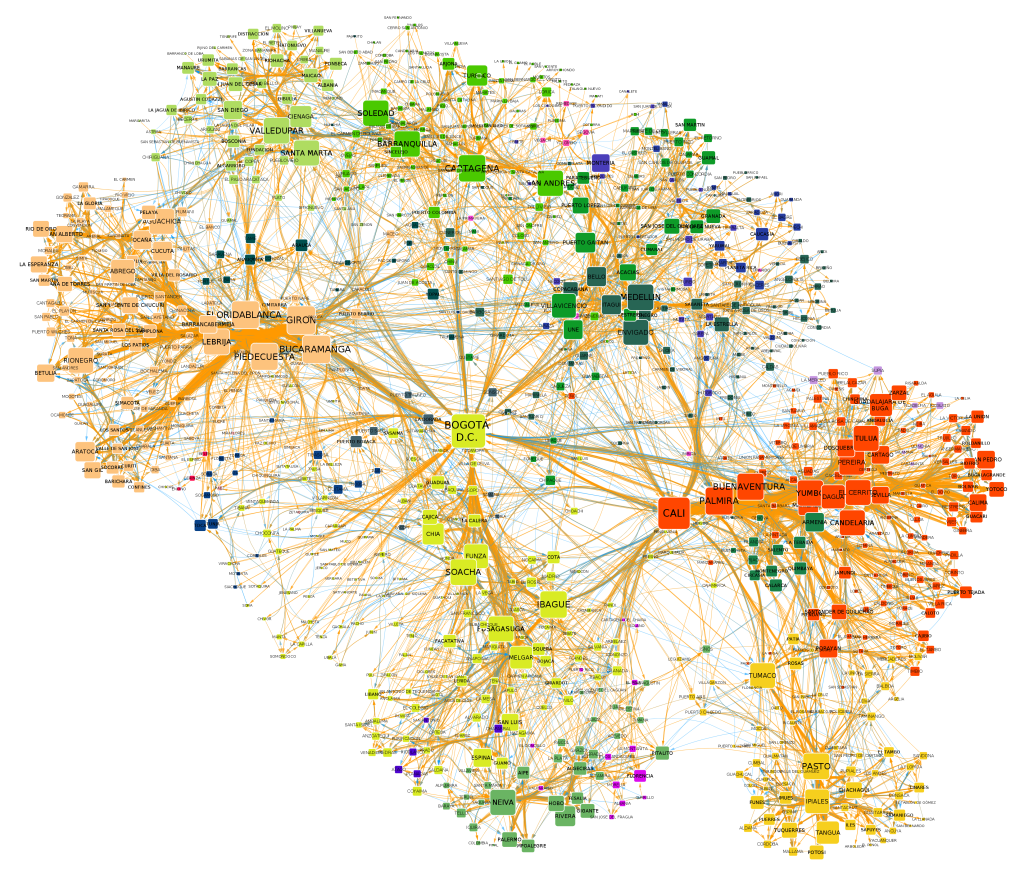

The latter is tricky, but not if you’re a data hoarder like yours truly. I had already worked with phone call records in Colombia, so you might guess where this is going. I can represent Colombia as a network, where nodes are the municipalities. Municipalities are connected to other municipalities if there is a significant number of residents in the two municipalities that call each other. Once I have this network, I can perform community discovery and find groups of municipalities with tightly knit social relations.

Colombia’s social network at the municipality level. Click to enlarge.

Using data on the municipalities’ GDP (from DANE) and average wage (from PILA), we can now test whether convergence happens — i.e. growth is negatively correlated with starting level, the poorer you are the more you grow. This is false for administrative regions but true for social communities: there is a mildly significant (p < 0.05) negative relationship between a social group’s GDP (and average wage) growth and its initial level. Meaning: economic convergence happens at the social but not at the institutional level. I’d love an even lower p-value, but one can’t do much with such a low number of regions/groups (32 in Colombia).

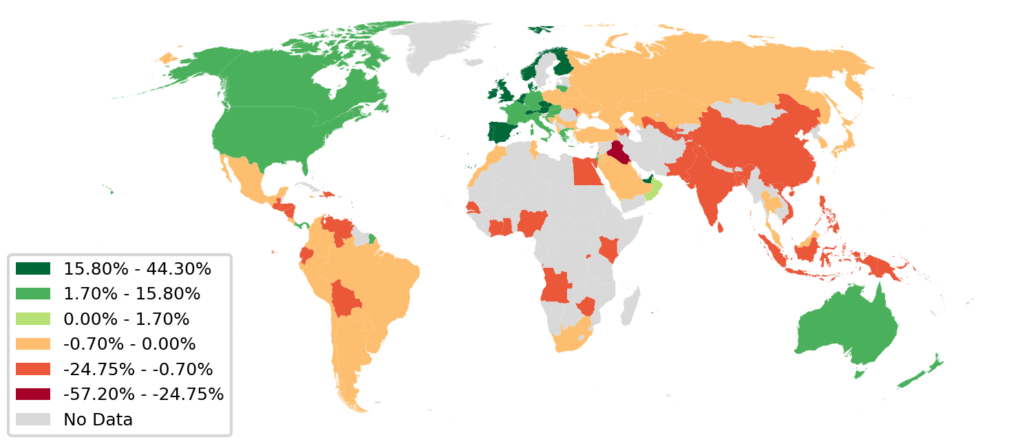

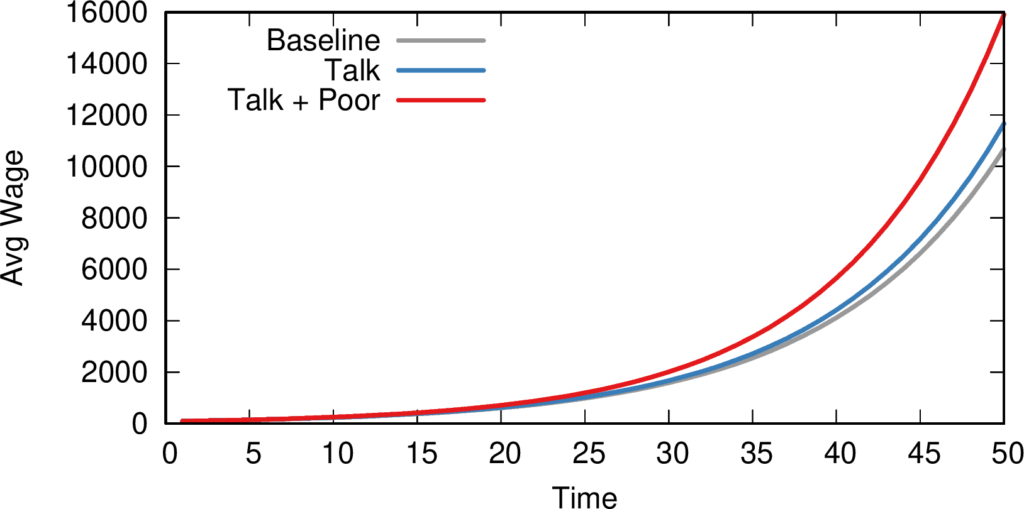

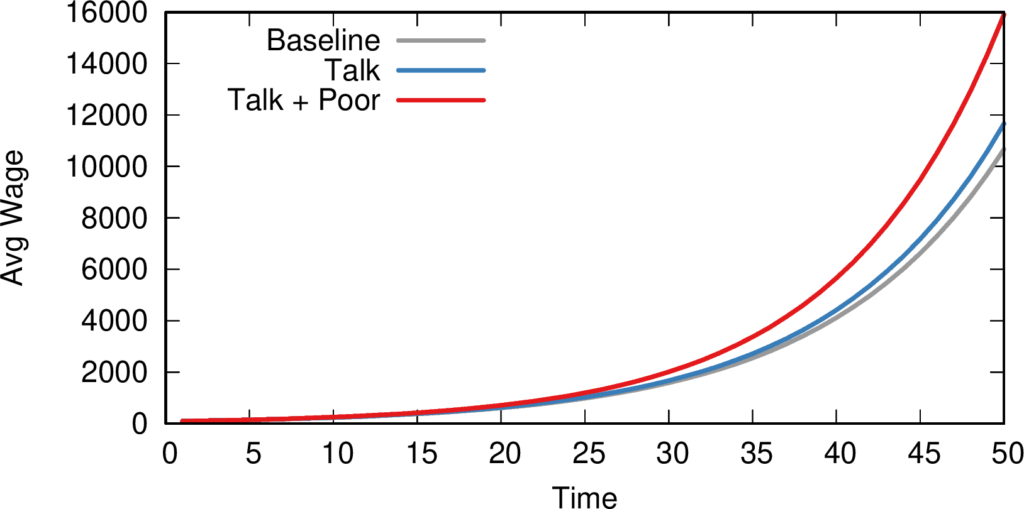

If social communities are converging, what could be driving the effect? We observe a robust (p < 0.01) positive relationship between the growth of per capita wages in a municipality and the average per capita wage in its social group. Meaning: if you talk to rich municipalities, you grow faster. Even the formality rate converges: if you talk with municipalities with low tax evasion, you start tax-evading less! Such relationships are absent for administrative regions, and survive a number of robustness checks — excluding the capital city Bogotá, excluding particularly small municipalities (in inhabitants, employees, or number of phone calls), using admin region fixed effects, etc. To get a sense of scale: suppose baseline growth is 1%. If you talk to a rich social group you’d grow, instead, by 1.02%. If you you talk to rich municipalities and you are also poor, you grow by 1.09% instead. This might not sound much, but it’s better to have it than not, and it stacks over time, as the picture below shows.

The effect of social relationships on average wage (y axis) over time (x axis). Gray = base growth; blue = growth while talking to rich social communities; red = talking to rich social community *and* being poor.

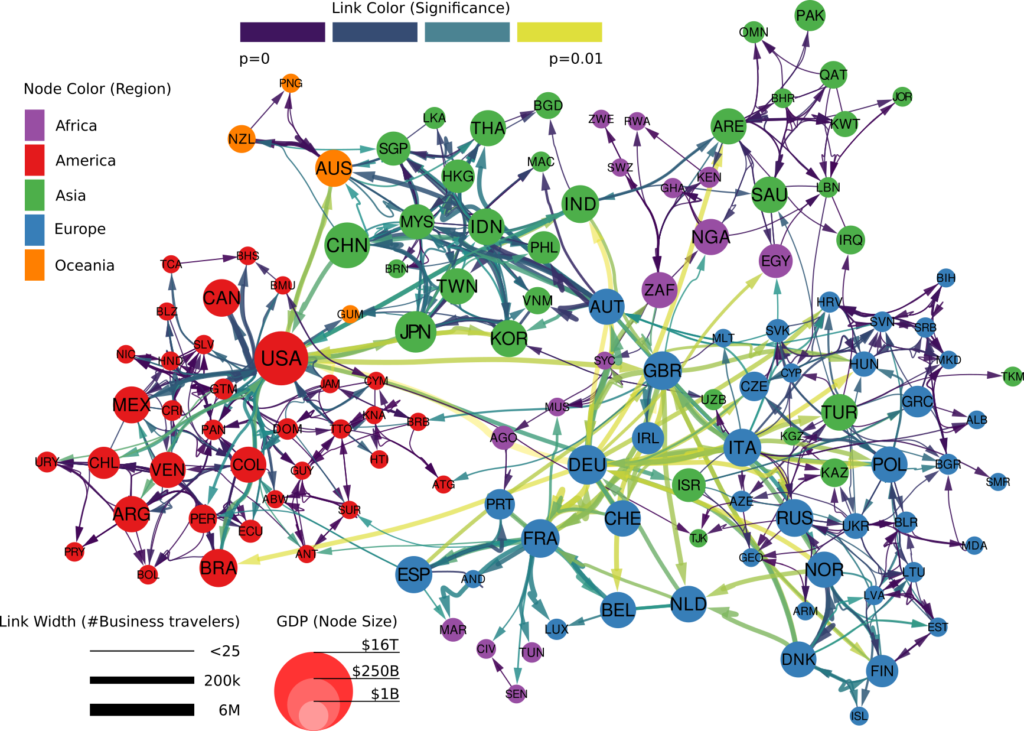

These results would be great in normal times, because they provide a possible roadmap to fostering economic convergence. One would have to identify places which lack the proper connections in the global knowledge network, and try to plug them in. The problem is that we’re not living in normal times. Lockdowns and quarantines due to the global pandemic have created gigantic obstacles to human mobility almost everywhere in the world. And, as I’ve shown previously, social relationships go hand in hand with mobility. For that reason, physical obstacles are also hampering the tightening of the global social network, one of the main highways of global development.

Don’t get me wrong: those are the correct measures and we should see them through. But we also should be mindful of their possible unintended side effects. Perhaps there are already enough people working on research on better medical devices, and on how to track and forecast outbreaks on the global social network. If this post has a moral, it’s to encourage people to find new ways to make the weaving of such global social network more robust to the black swan events that will follow COVID-19. Because they will happen, and our moral imperative of lifting people out of poverty can’t be the price we pay to survive them.

* This needs to be a structural intervention: simple handouts don’t work and may even make the problem worse.

Continue Reading