The Glass Door of Wikipedia’s Notable People

I think Wikipedia is great. I spend tons of time on it. I especially like to read about history, because it allows me to quickly jump into obscure details about anything, without the need to scout for specialized literature that might be super hard to find. But one question always creeps in the back of my mind: am I reading something as fair as it can be? How much are the editors’ biases driving my discovery process? These are testable questions! And the subject of this blog post, and a paper I recently published.

The paper is “Traces Of Unequal Entry Requirement For Illustrious People On Wikipedia Based On Their Gender” recently published in the Advances in Complex Systems journal. This is mostly the product of brilliant Lea Krivaa‘s master thesis. In the paper, we decided to focus on a specific bias: the role gender plays in the inclusion criteria of notable people on Wikipedia.

The hypothesis is that women need to do more than men to “deserve” a Wikipedia page. The are a few problems with this hypothesis. For starters, we can’t really prove it by simply saying that there are way more men than women on Wikipedia. That can happen and still be fair, because Wikipedia is just working with whatever it can collect from the notoriously male-centric historiography. Moreover, a true fairness test is hard to make: it’s not feasible to collect from the already-biased archives every person’s CV and see that there are discarded CVs from women that are as good as some of the included men on Wikipedia. Good luck checking the Roman Empire CVs after the Visigoths sacked the capital in 410AD.

However, it turns out that we can find traces of this glass entrance door by using some unexpected network science techniques. We built a network of notable people: we took the set of people from Pantheon, because it’s a curated list of people that are on multiple language Wikipedia editions — this ensures they’re not just a pet peeve of some local editor. Then we connected them with an edge if the page of one person has a hyperlink connecting it to the page of another.

Crucially, we’re able to estimate the weight of the edge with some natural language processing: we count the number of times the target of this hyperlink is mentioned in the page containing the link. Knowing the edge weight is fundamental, because then we can use my backboning method to know the significance of this weight: how likely is it to be a noisy link?

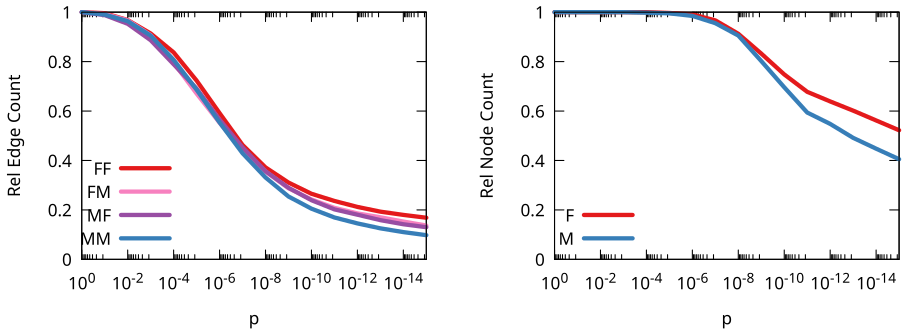

Backboning is done to sparsify a network, by dropping the least significant edges. But here we’re just interested in looking at the significance values themselves. By looking at them we discover something odd: the edges involving women are on average more significant. If we were to establish a high significance threshold, we would end up isolating (and dropping) way more men than women. This shouldn’t happen if there was no bias.

Our interpretation is that this is a hint that the glass entrance door exist: to be included in multiple language Wikipedias, a woman needs to have more significant ties with other notable people than a man.

This might seem a stretch or a bit abstract, but there’s a neat way to test this interpretation. On March, Wikipedia has a tradition of celebrating the month by improving its coverage of notable women. This means that, in March, it is “easier” for a woman to get added to Wikipedia than normal. And we can confirm this with our analysis! If we only look at pages created in March, the gap we observe is noticeably smaller.

Of course all of this should be taken with a grain of salt. Since we rely on Pantheon’s curation of profiles, we inherit all of their biases. Moreover, we only focus on the 1750-1950 time period, for various data quality reasons. And there are other factors affecting how much we can read in this analysis. For instance it might be that we simply do not have enough women to include in Wikipedia, because of the male bias in historiography I already mentioned. However, we think this is an interesting question to ask, because we can do better to improve inclusivity. If the gap can shrink in March, we ask: why can’t it shrink the whole year around?