The Supermarket is an Ecosystem

There are few things that you would consider less interesting than doing groceries at the supermarket. For some it’s a chore, others probably like it. But for sure you don’t see much of a meaning behind it. It’s not that you sense around you a grave atmosphere, the kind of mysterious background radiance you perceive when you feel part of Something Bigger. Just buy the bloody noodles already. Well, to some extent you are wrong.

(Image from “Hungry Planet: What the World Eats“)

Of course the reality is less mystical than what I tried to led you to believe in this opening paragraph. But it turns out that customers of a supermarket chain behave as if they were playing a specific role. These roles are the focus of the paper I recently authored with Diego Pennacchioli, Salvatore Rinzivillo, Dino Pedreschi and Fosca Giannotti. It has been published on the journal EPJ Data Science, and you can read it for free.

So what are these roles? The title of the paper is very telling: the retail market is a complex system. So the first thing to clear out is what the heck a complex system is. This is not so easily explained – otherwise it wouldn’t be complex, duh. The precise physics definition of complex systems might be too sophisticated. For this post, it will be sufficient to use the following one: a complex system is a collection of interacting parts and its behavior cannot be expressed as a sum of the behaviors of its parts. A good example of complexity is Earth’s ecosystem: there are so many interacting animals and phenomena that having a perfect description of it by just listing all interactions is just impossible.

And a supermarket is basically the same. In the paper we propose several proofs of it, but the one that goes best with the chosen example involves the esoteric word “nestedness”. When studying different ecosystems, some smart dudes decided to record their observations in matrix form. For each different island (ecosystem) they recorded if a particular species was present or not. When they looked at the resulting matrix they noticed a particular pattern. The islands with few species had only the species that were found in all islands, and at the same time the most rare species were present exclusively in those islands which were hosting all the observed species. If you reordered the islands by species count and the species by island count, the matrix had a particular triangular shape. They called matrices like that “nested”.

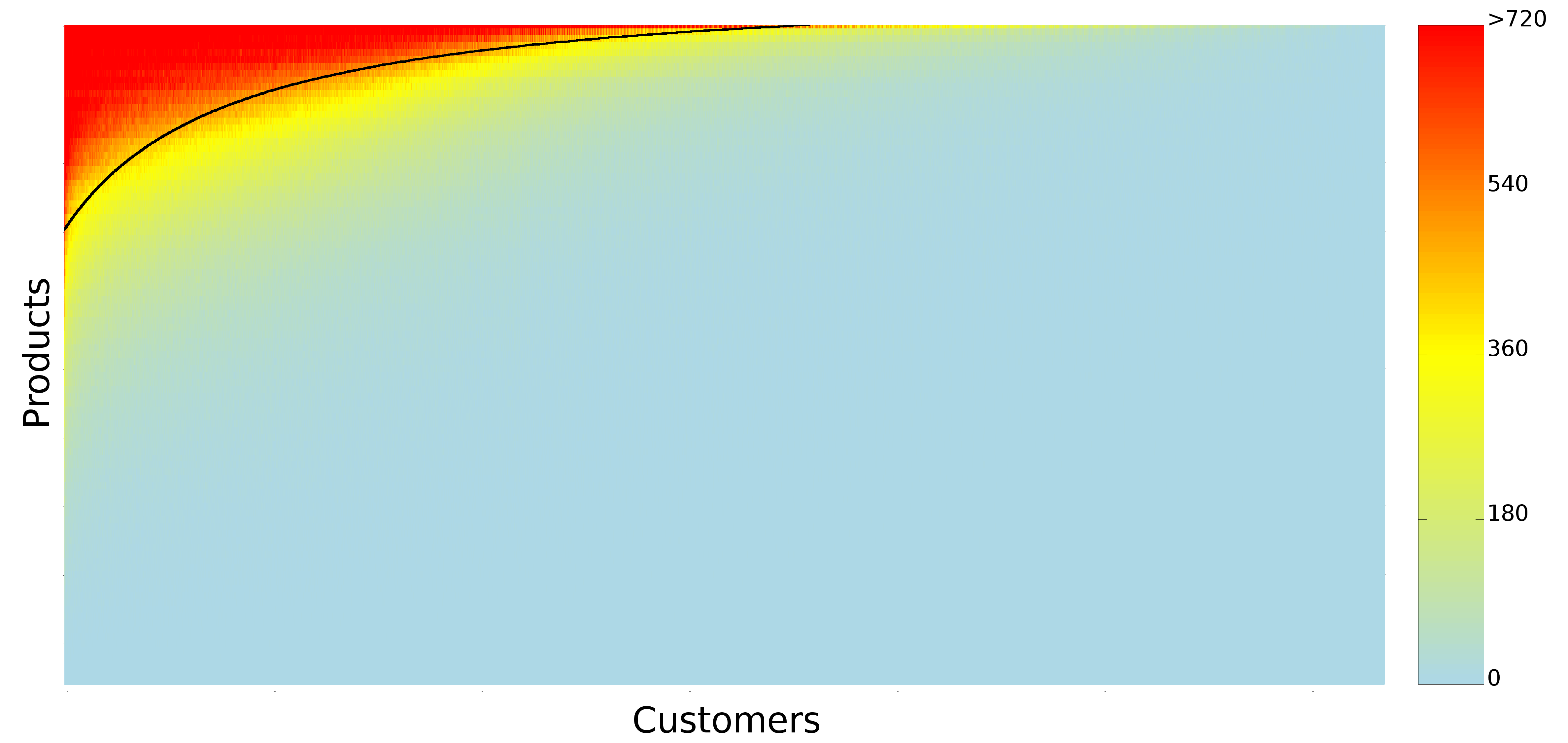

We did the same thing with customers and products. There are customers who buy only a handful of products: milk, water, bread. And those products are the products that everybody buys. Then there are those customers who, over a year, buy basically everything you can see in a supermarket. And they are the only ones buying the least sold products. The customers X products matrix ends up looking exactly like an ecosystem nested matrix (you probably already saw it over a year ago on this blog – in fact, this work builds on the one I wrote about back then, but the matrix picture is much prettier, thanks to Diego Pennacchioli):

Since we have too many products and customers, this is a compressed view and the color tells you how many observations we have per pixel (click for full resolution). One observation is simply a pairing of a customer and a product, indicating that the customer bought that product in significant quantities over a year. Ok, where does this bring us? First, as parts of a complex system, customers are not so easily classifiable. Marketing is all about finding uniformly behaving groups of people. The consequence of being complex parts is that this task is hopeless. You cannot really put people into bins. People are part of a continuous space, as shown in the picture, and every cut-off you propose is necessarily arbitrary.

The solution to this problem is represented by that black line you see on the matrix. That line is trying to divide the matrix in two parts: a part where we mostly have ones, and a part where we mostly have zeroes. The line does not match reality perfectly. It is a hyperbola that we told to fit itself as snugly to the data as possible. Once estimated, the function of the black line enables a neat application: to predict the next product a customer is interested in buying.

Remember that the matrix has its columns and rows sorted. The first customer is the one who bought the most products, the second bought a little less product and so on with increasing ranks. Same thing with products: the highest ranked (1st) is sold to most customers, the lowest ranked is sold to just one customer. This means that if you have the black line formula and the rank of a customer, you can calculate the rank of a corresponding product. Given that the black line divides the ones from the zeros, this product is a zero that can most easily become a one or, in other words, the supermarket’s best bet of what product the customer is most likely to want to buy next. You do not need customer segmentation any more: since the matrix is and will always be nested you just have to fill it following the nested pattern, and the black line is your roadmap.

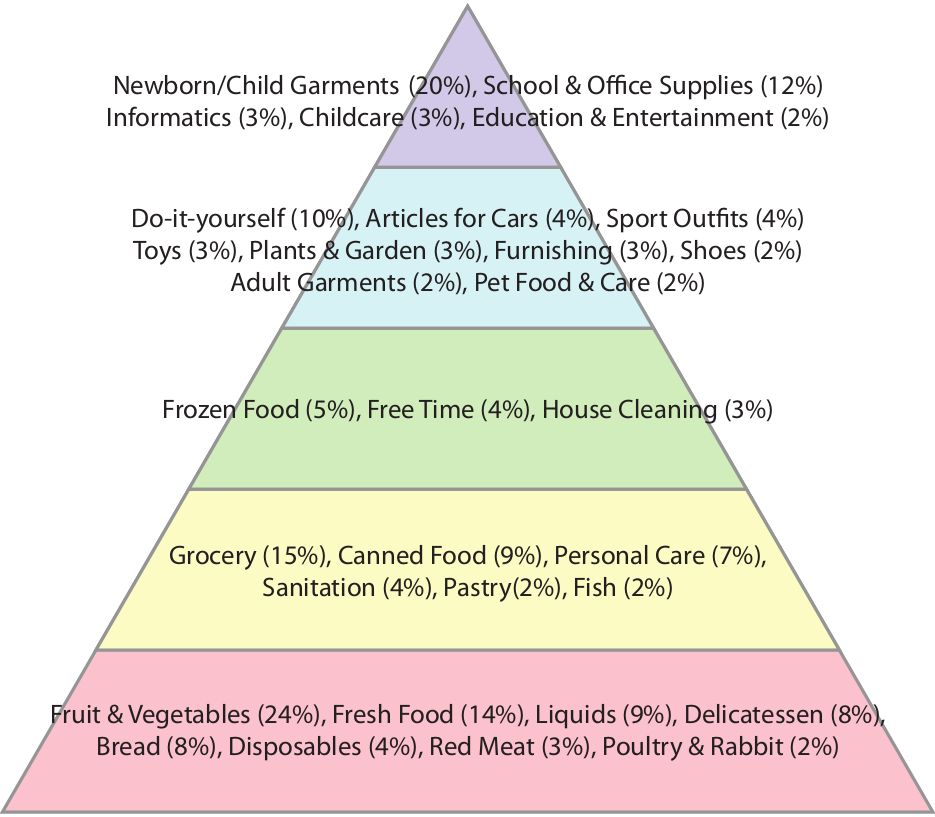

We can use the ranks of the products for a description of customer’s needs. The highest ranked products are bought by everyone, so they are satisfying basic needs. We decided to depict this concept borrowing Maslow’s pyramid of needs. The one reported above is interesting (again, click for full resolution), although it applies only to the supermarket area our data is coming from. In any case it is interesting how some things that are on the basis of Maslow’s pyramid are on top of our, for example having a baby. You could argue that many people do not buy those products in a supermarket, but we address these concerns in the paper.

So next time you are pondering whether buying or not buying that box of six donuts remember: you are part of a gigantic system and the little weight you might gain is insignificant compared to the beautiful role you are playing. So go for it, eat the hell out of those bad boys.