Hitting the Front Page Triggers an Evolutionary Arms Race

I’m a conformist. Just like everyone else in computer science working on memes, I am lured by the Holy Grail of questions. Can I figure out what makes content go viral? I really want to answer “yes”, but my absence from Reddit’s front page speaks louder than any advice I could give to you. That didn’t dissuade me from trying to look for a question fitting my preferred answer. After building Earth and waiting a few billion years for it to process the question, this is what I got: “can I figure out what makes content not go viral?” I guess that’s half of the job, right?

In 2014 I proposed my explanation, a rather trivial one: the content that does not go viral is the one that is unoriginal, the one that is too close a copy of something that is already out there. My explanation sounds uncontroversial: to be successful you have to be original, yeah thank you very much. But there was a little problem with it: karma trains. Very often, topics stay popular multiple days: Reddit and social media are flooded with posts about the same thing, seemingly tapping into a neverending pit of attention and upvotes. Unoriginal content actually makes it to the front page. Was it time to throw my theory in the dustbin?* I didn’t think so. So, in this month’s issue of Communications of the ACM, I published a sequel: “Popularity Spikes Hurt Future Chances for Viral Propagation of Protomemes.”

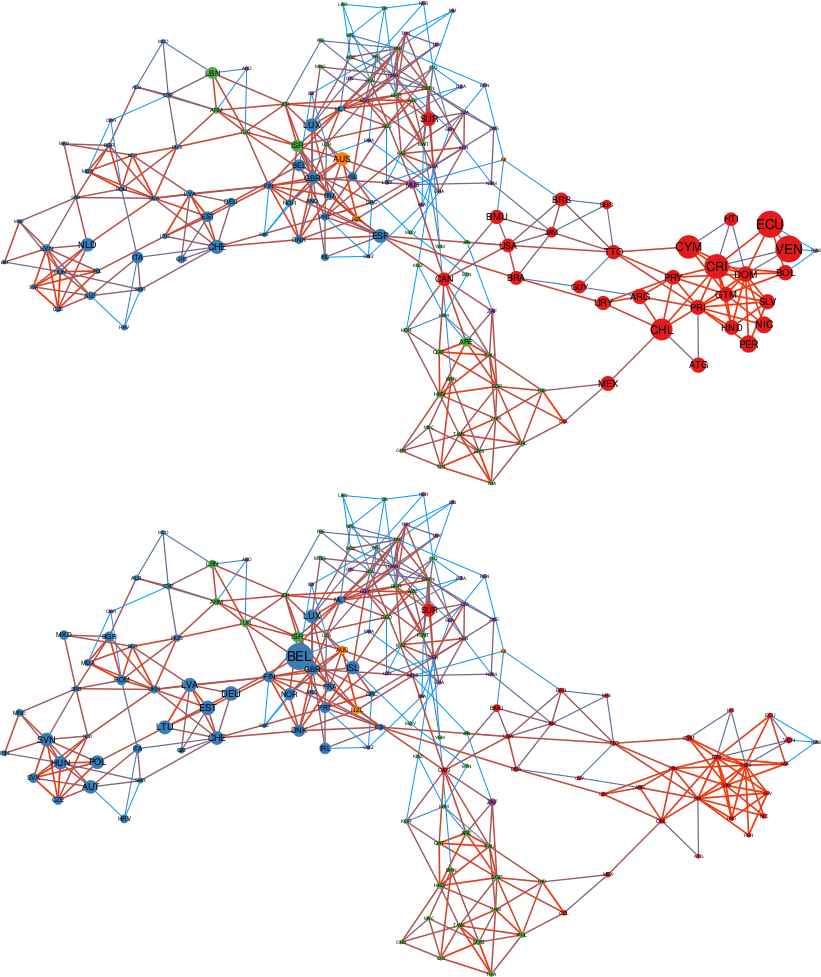

I need to defuse the danger that karma trains represent for my theory, and I do so in two parts, asking two questions. First: is it really true that, in karma trains, content that stays closer to the original post gets more attention and success? Second: is it really true that karma trains contain exclusively unoriginal content? For these questions, I define specifically karma trains to be the collection of posts using a meme after it hit the front page. To answer these questions I focus mainly on Reddit. I use data kindly donated to me by Tim Weninger from the University of Notre Dame (in particular from this paper of his). I look at all catchphrases used frequently — hence the word “protomeme” in the title: my definition is a bit wider than just memes — and I track down how successful they are in each day.

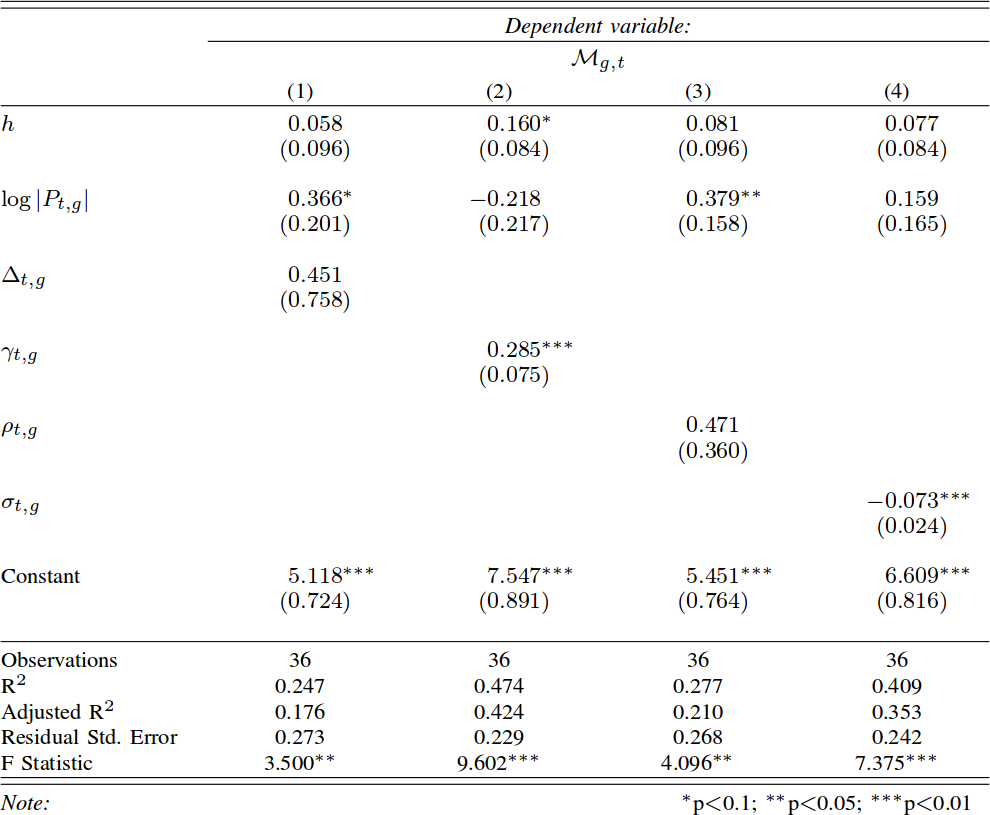

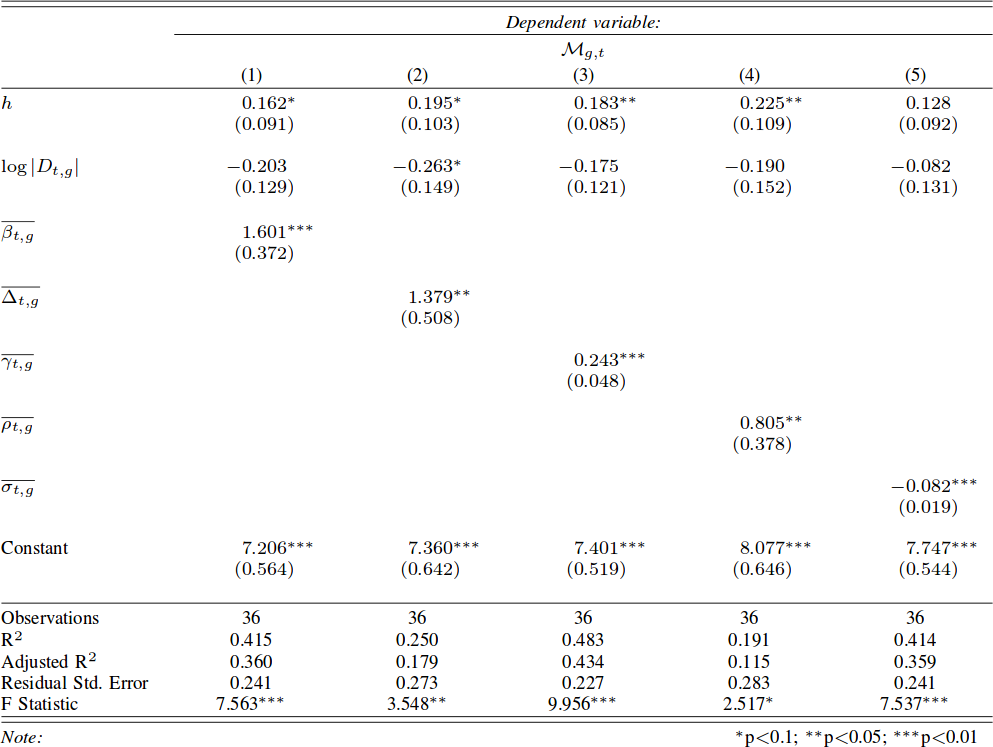

For the first question I have to debunk the notion that unoriginal content is successful in karma trains. First, I check if a meme hit the front page on a particular day. Then I look at all the Reddit posts containing that meme the day after. A karma train implies that more people will use the meme — so, more posts using the catchphrase — and that posts including the meme will be on average more successful. The first part is true: karma trains do exist and, after a meme hits the front page, more people will use it. But the second part is crucially false: on average these posts score poorly. This is not just regression towards the mean: obviously if the meme just hit the front page, its average popularity the day after can only go down. But I control for that. I control for the entire history of the meme. Its average popularity the day after hitting the front page is significantly lower than its regular average popularity, its recent popularity trends, and the average popularity of everything else that day.

So what gives? If the meme is doing poorly, why are karma trains a thing? Because, over those many attempts, a few are going to hit the front page again. Since the front page is very noticeable, we’re tricked into thinking that all posts using the meme are doing well. This transitions nicely into the second part of the paper. Why are those few posts successful? Bell-shaped random distributions teach us that, if you try enough times, one of the attempts is going to be really good. Is that the case? Are we looking at statistical aberrations or is there something interesting? There is: these posts are not ending up on the top randomly. There’s something special about them.

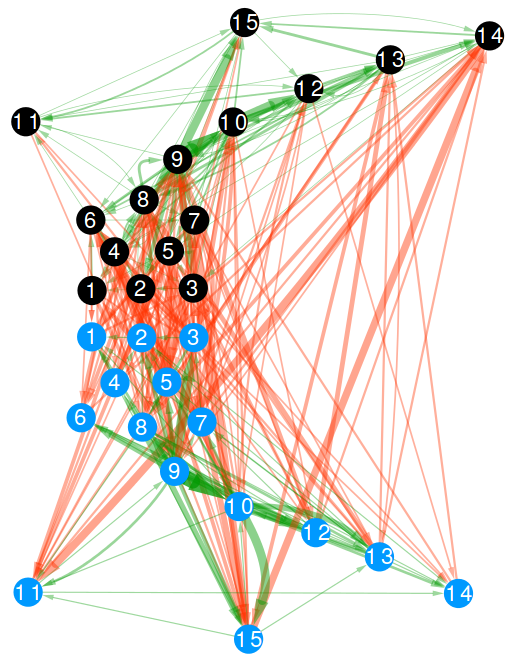

I made up a measure of post originality. Given that a post contains a meme, I want to know if it is repeating it in a boring way, or if it is adding something to the mix. It answers the question: how canonical is the usage of the meme in this post? That is why I called this measure “canonicity”. In practice, for every word that ever appeared in a Reddit title, I calculate the probability that the word is going to be used in a post including that meme. So for every new post I can calculate the average word probability, and ending up with an estimation of how surprising this particular post title is.

You know what I’m going to say next. The more unsuprising a post is, the less likely it is to be successful. A high-canonicity post has roughly half the odds of being widely successful — e.g. hitting the front page — than a low-canonicity one. And the fact that there are low-canonicity posts in karma trains is interesting of itself. It confirms my hunch that, among the posts that jump on the bandwagon of popular memes, there are also original thoughts. This is the evolutionary arms race I mention in the title: when a meme hits the front page, subsequent implementations of it have to constantly innovate, else the meme will be infested by high-canonicity copies, and fade into oblivion. This is generally true for all memes, but it is an effect on steroids for recently successful memes, because they are the ones that are being copied the most in a particular time period.

The story has another interesting turn. Low-canonicity is a double-edged sword. It gives you better odds to hit the front page, but if you fail at it then your performance is going to be atrocious. In that case, high-canonicity posts are actually doing better than low-canonicity ones. In other words, a meme after hitting the front page does a sort of “canonicity sandwich”: the very best AND very worst posts are low-canonicity ones, and in the middle you have high-canonicity posts. Why does this happen? Maybe it’s because of familiarity. Familiar content is reassuring and so people “get it” and upvote. It just does not soar high enough. Or it can be a million other reasons that I haven’t tested yet, so I can only speculate.

What the canonicity sandwich means is that content originality has a varying effect: high canonicity harms you in some cases, but it’s good for you in others. This discovery is important, because other researchers have found that a post’s content doesn’t seem to explain its success very well. The sandwich effect might very well be the cause of our disagreement.

To wrap up, I hope I put on a credible defense of my theory in the face of karma trains. These annoying meme critters are dangerous to my explanation of popularity, because they directly contradict it. Karma trains seems to be a collection of popular unoriginal content: the exact thing my theory says it shouldn’t exist. Upon closer inspection, I noticed that (a) it isn’t really true that karma train posts are particularly successful and (b) it isn’t really true that they only contain unoriginal content. So, my theory is going to die another day, like in all good James Bond flicks**.

* Yes, but I need tenure, so I’ll have to put up a fight.

** Which Die Another Day wasn’t.

I am an associate prof at IT University of Copenhagen. I mainly work on algorithms for the analysis of complex networks, and on applying the extracted knowledge to a variety of problems.

My background is in Digital Humanities, i.e. the connection between the unstructured knowledge and the coldness of computer science.

I have a PhD in Computer Science, obtained in June 2012 at the University of Pisa. In the past, I visited Barabasi's CCNR at Northeastern University, and worked for 6 years at CID, Harvard University.

I am an associate prof at IT University of Copenhagen. I mainly work on algorithms for the analysis of complex networks, and on applying the extracted knowledge to a variety of problems.

My background is in Digital Humanities, i.e. the connection between the unstructured knowledge and the coldness of computer science.

I have a PhD in Computer Science, obtained in June 2012 at the University of Pisa. In the past, I visited Barabasi's CCNR at Northeastern University, and worked for 6 years at CID, Harvard University.